Perhaps coming to art from a science and technology background I am naturally drawn to the structure and order of geometric abstraction (see note below). From time to time in my art career I have returned to science and technology as a source of inspiration and regeneration. In 2005 I used computer graphics to make my own “Chromatic Accelerators” inspired by Canadian artist Claude Tousignant to enliven my home gym.

Art and science share common processes of inquiry, experimentation, visualization, theory construction, testing and revision. Both science and art work within, yet outside of, the bounds of socio-political environment, with the aim of pushing boundaries of knowledge and understanding (Stephen Wilson, Art + Science Now, 2010).

In my studies of art history I discovered that many great artists, most notably being Leonardo Da Vinci, recognized the interrelationships between art, science and technology. I have been inspired by two Modern artists in my forays into geometric abstraction. The first is Sol LeWitt (1928-2007) an American Minimalist and Conceptual artist, and the second is Kazuo Nakamura (1926-2002), an Abstract Expressionist landscape painter who sought to reveal the underlying fundamental structures of nature. Nakamura was thoughtful and rational about his work and avidly sought integration of science and art to reveal the underpinnings of nature rather like the scientists that were revealing new knowledge about the atomic structure of matter in the mid twentieth century.

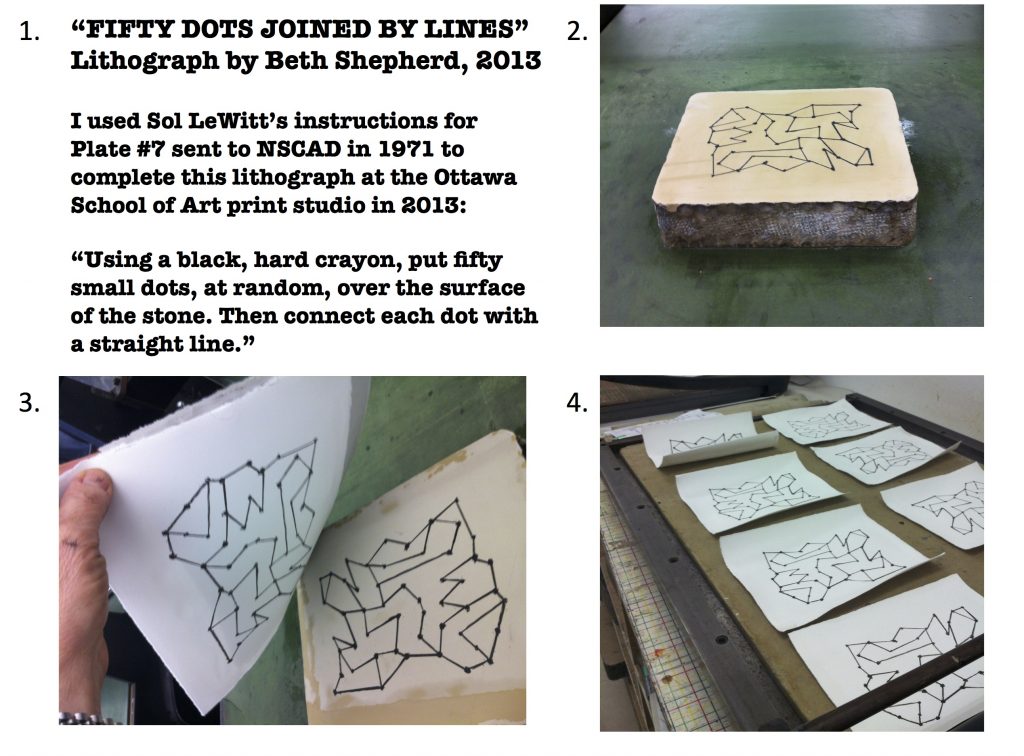

Sol LeWitt started his career as a graphics designer and his early work in the field of architecture influenced his both his use of two- and three-dimensional structures and his attitude about the artistic process. As in architecture, LeWitt separated the concept planning stage from the execution stage in his art practice. To that end, he provided instructions to others to execute his geometric projects and became best know for his instruction-based wall art.

As part of an art history essay I was writing — “Sol LeWitt: Work from Instructions” — I undertook to do my own Sol LeWitt work of art, working from his written instructions used in project he did with the Nova Scotia College of Arts and Design. Just as NSCAD students working with the master printers produced a series of lithographic prints in 1971, I produced my own rendition of one of these works while learning lithography at the Ottawa School of Art in 2013.

Concurrently in my art practice I was beginning a project on Geometric Art inspired by the work of Dutch artist and printmaker Michael Berkhemer (b. 1948), called Works in Progress (2002). Berkhemer’s large prints were simple and clean in form–just lines–but complex in the use of pattern and colour. I recalled a great Sol LeWitt quote: “Obviously a drawing of a person is not a real person, but a drawing of a line is a real line” (Sol LeWitt, in an interview by Andrew Wilson, Art Monthly, 1993). I also thought of how important the line is metaphorically: Don’t cross that line, the end of the line, tow the line, what’s my line, hold the line, deadline, flat line, red line, by-line, beeline, infinite line… and the possibilities seemed endless! The light came on – I had the idea that gave rise to my ongoing body of conceptual geometric abstraction I call Line Work.

Here are a couple of examples.

Creating and perceiving art have a lot to do with personality. Not everybody will like the same things. I believe that art is not just about pleasing the eye or releasing emotions but like Sol LeWitt and Kazuo Nakamura, I believe that art should stimulate the mind of the viewer. I hope my art and essay achieve this end. Let me know.

Geometric Abstraction: refers to the use of simple geometric forms placed in non-illusionistic space combined into nonobjective compositions. It in its many forms evolved out of the Cubist process of purifying art by removal of the vestiges of visual reality and focusing on the inherent two-dimensional nature of painting. Geometric abstraction took many forms in Western Modern Art: Malevich’s Suprematism in Russia, Mondrian’s Neoplasticism and Bauhaus influences in Europe, peaking with Minimalist art of the 1960s. (Magdalena Dabrowski, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004).