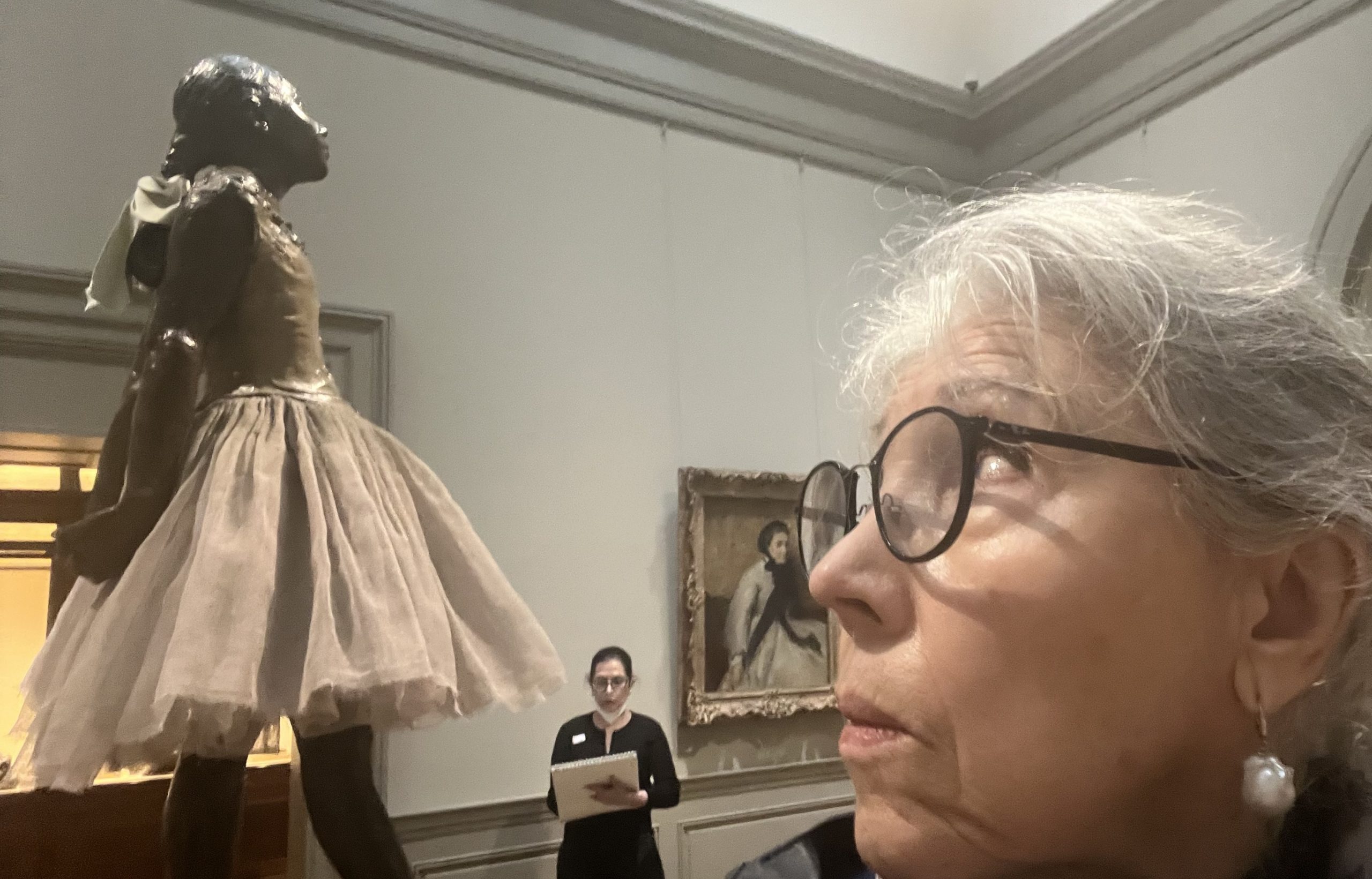

In March 2023 I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and had the pleasure of seeing Edgar Degas’s The Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (circa 1878-81; cast A.A. Herbrard, 1922 (Paris)). I have seen this sculpture a number of times and I am always struck by its uniqueness — the contrasting materiality of durable bronze and the fragility of the tattered tutu and silk hair ribbon. I was especially pleased this time at the attractiveness of the little dancer’s new tutu.

A few years before my last visit, Glen Peterson, conservator at the Met, had been charged with researching what dancers wore when the original sculpture was created to make the tutu more historically accurate. Peterson determined that the bouffant skirts worn by ballerinas of the day were knee-length and made of multiple layers of tarlatan, a starched open-weave cotton. He painstakingly hand-crafted the new longer tutu which was installed in 2018 (1).

Edgar Degas (1834-1917) is not recognized as a sculptor but as an impressionist painter in oils and pastels. Nevertheless, he did undertake some sculpture in wax and clay of his favourite subjects: ballerinas, nudes, and horses. He exhibited La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans at the sixth Impressionist exhibition held in Paris in 1881. Like the Impressionist paintings of his peers, Degas’s work broke many conventions of classical art of the period. Even more controversial, the sculpture was modelled in wax and wore a real bodice, stockings, shoes, a tulle skirt, and a hair wig with a satin ribbon – materials not used in fine art. Everything but the tutu and ribbon was set in wax (2). The work received much criticism and the sculpture was not shown again during Degas’s lifetime.

Upon Degas’s death in 1917, La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans and other sculptural pieces were found in his studio. His heirs authorized a series of bronze casts to be made at the Paris foundry of A. A. Hébrard et Cie. It is not certain how many copies of La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans were made but they may be found in many gallery collections. The original wax sculpture is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Camille Laurens in her recent book Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, addresses the life of Degas’s subject, Marie van Goethem (1865-unknown) ― a young girl from a poor family living in Paris and training at the Paris Opera with hopes of a better life. While at the Opera, Marie was engaged to model for Degas. In late 19th century Paris it was common for young dancers and models to be subjected to sexual abuse by older male artists. Degas was known to be a celibate misogynist and therefore very unlikely to have forced himself sexually on his model; nevertheless, their relationship would have been fraught with gendered power imbalances (3).

Ballet in 19th century Paris was not the refined high-brow art form we know today. Girls as young as eight years old became ballerinas, working ten to twelve hours a day, six to seven days a week engaged in strenuous rehearsals, performances, and other related chores. After reaching “sexual maturity” at thirteen, girls were often paid to have sex with men waiting in the opera’s wings. The girls were nicknamed “les petits rats” because they were known to transmit STDs. Degas’s disdain for women, and in particular ballet dancers, is sculpted into Marie’s features to portray moral degeneracy rather than a youthful vibrancy. Audiences derided the ugliness of the pigmented beeswax and clothing and the subject herself (3).

In searching through the Paris Opera’s account books, Laurens found that in 1882, a year after the completion of Degas’s sculpture, Marie was docked in pay due to absence and eventually fired from her dancing post (possibly due to time spent modelling for Degas?) (3). After that, the real little dancer is lost to history.

I made two prints for the Expressive Movement: Dance, Rhythm and Flow Exhibition at the Connective Gallery in the Nepean Creative Arts Centre, March 4 to June 24, 2024. The first, Little Dancer, is a drypoint print after a photo I took of the sculpture at the Met in 2023. I printed it with black ink and collaged some pink Mizutama tissue covering the bodice and tutu. I wanted to bring her to life!

Drypoint and collage

8×6 inches

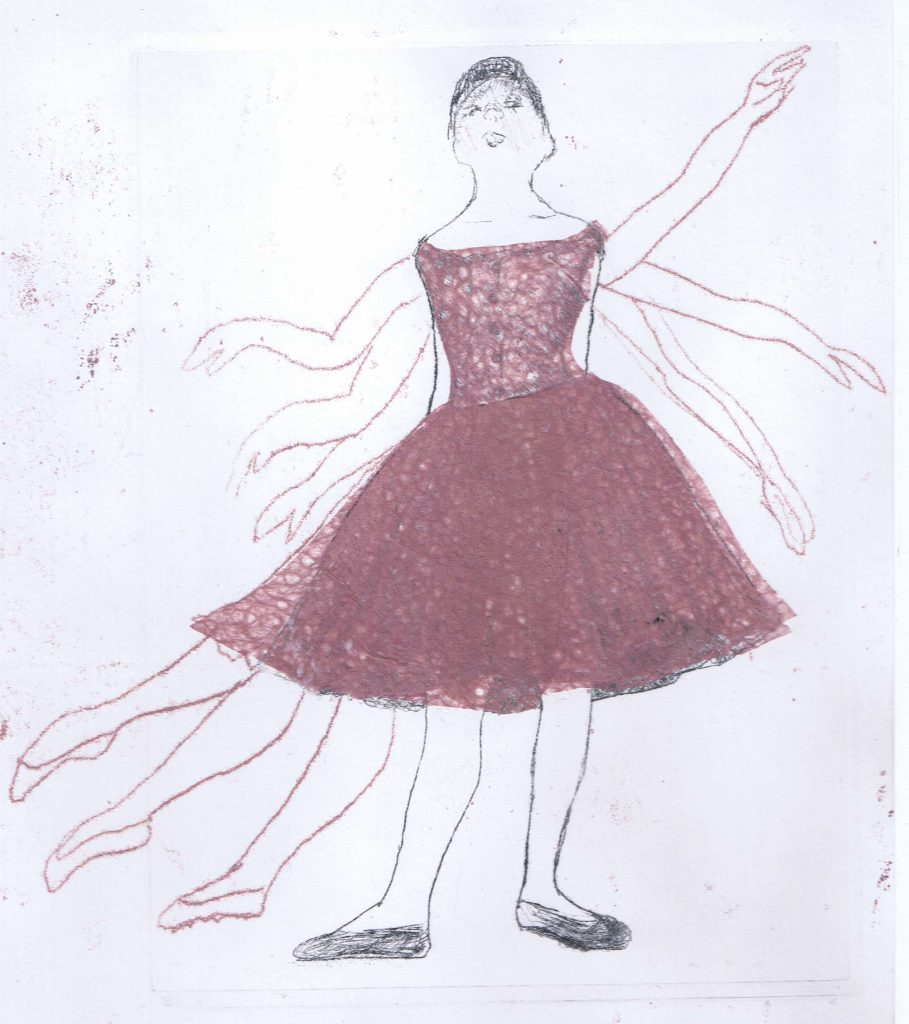

At the same time that Degas was working on the Little Dancer sculpture, Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey were experimenting with photography to help understand animals and humans in motion. Marey, a physiologist, invented a camera system that allowed the capture of movement on a single plate called chronophotography (4). In Little Dancer Redux, I imagine Marie revived, leaving her static fourth position pose, and lifting her right leg up while extending both her arms outward. I represent each moving limb in three positions as if captured with chronophotography. To differentiate the imagined movements from the original print, I used a trace monotype technique and pink ink.

Drypoint, trace monotype, and collage

9 ½ x 7 ½ inches

It is my hope that by celebrating The Little Dancer Aged Fourteen we are paying tribute to this young person whose life history is lost but who lives in the minds of all that see her. To Marie van Goethem!

References:

(1) The Met, Conserving Degas, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Swh6pYdeR_8.

(2) Clare Vincent, “Edgar Degas (1834–1917): Bronze Sculpture.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–(October 2004). . http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dgsb/hd_dgsb.htm .

(3) Priscilla Frank, “The Story Of Degas’ ‘Little Dancer’ Is Disturbing, But Not In The Way You Expect”, Huffpost, Nov 21, 2018, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/degas-little-dancer-camille-laurens_n_5bec3dc5e4b0783e0a1ed801. The article references Camille Laurens, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen: The True Story behind Degas’s Masterpiece. Translated by Willard Wood, Other Press, 2020.

(4) Étienne-Jules Marey, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Étienne-Jules_Marey.